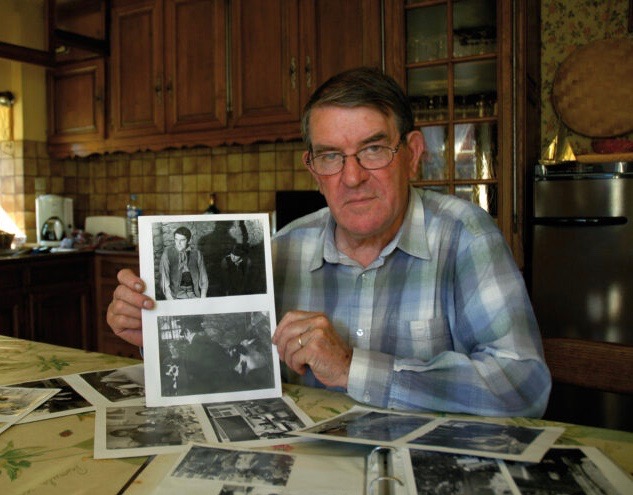

Self-portrait of Nicolas Philibert as a filmmaker

What is the cinema? This open, vast and demanding question sums up the essence of Nicholas Philibert’s Retour en Normandie better than any synopsis. After Être et avoir (To Be and To Have, 2002), focused on its tiny classroom, this new film, spread out over time and space, is impossible to relate, except in fragments.

One can say that it’s a documentary. That it revolves around another film, René Allio’s I, Pierre Rivière, Having Slaughtered My Mother, My Sister and My Brother..., on which Nicolas Philibert worked as first assistant director thirty years ago. One can say that it is consistently surprising without ever being disturbing and that, as a direct descendant of the previous film, it pierces some astonishing holes in time. And that it is a dazzling meteorite in the Cannes 2007 harvest.

The origins of Retour en Normandie lie in Philibert’s desire to return to the locations of Allio’s film on which he took his first steps in the cinema, in order to see the people that he had convinced at the time to become actors, to find out what has become of them and to see what memories they have of the film. He also wanted to remind audiences of the specificity of that film: a period fiction work, performed by local farmers and adapted from a collective work edited by Michel Foucault on the “case” of Pierre Rivière.

In Normandy, in the 19th century, this young man killed his mother, his sister and his brother before being sentenced to death and then pardoned. He ended up committing suicide, but not before leaving the world a poignant manuscript outlining the reasons that led him to commit this triple murder. The approach recalls that of Hervé Le Roux who, in his fine film Reprise, set off in 1995 to find a woman he had seen in a short film dating from 1968 on the return to work at the Wonder factory. But the aim of Retour en Normandie is both much vaster and more intimate because, through this multi-layered story, Nicolas Philibert provides us with nothing less than his own self-portrait as a filmmaker.

The heart of the film beats at several different speeds and takes in the history of ideas, social struggles and the peasantry, along with that of madness and the cinema. The former actors in the film have returned to their “normal” lives but their stories all strike a chord with René Allio’s film. Retour en Normandie opens on a farmer assisting the birth of a litter of piglets, one of which he brings out of a coma; a woman works in a centre for mentally handicapped adults; a couple talks about the way in which their daughter sank into psychosis; a militant anti-global baker’s wife struggles against aphasia… Not one of them has performed in another film since then, except for Claude Hébert who played Pierre Rivière and who, after a brief but promising career, vanished without a trace. Like a gaping hole in the film, his absence gradually creates genuine s.uspense

Between interviews, the director roams around. He visits the library that holds René Allio’s archives, reads extracts from his diary in voice-over, goes to the prison where Pierre Rivière took his life, follows a procession of anti-nuclear demonstrators and calls in at the Éclair film laboratory whose existence has been under threat since its acquisition by a pension fund.

While giving a continual impression of being sidetracked, the filmmaker builds up a moving and poetic work that is clearly focused in spite of its kaleidoscopic nature. Slender threads run from one section to another. They are called utopia, commitment, art, marginality, humanism or ethics and originate in Allio’s film before irrigating Philibert’s.

In laying claim to this legacy, but also to that of his father, who occupies the last frame of Retour en Normandie, Nicolas Philibert sketches out a reply to the question “What is the cinema?” It could be a story of inheritance, of lone creators and collective creation, of the seizing of a breath of life. A mild form of madness.