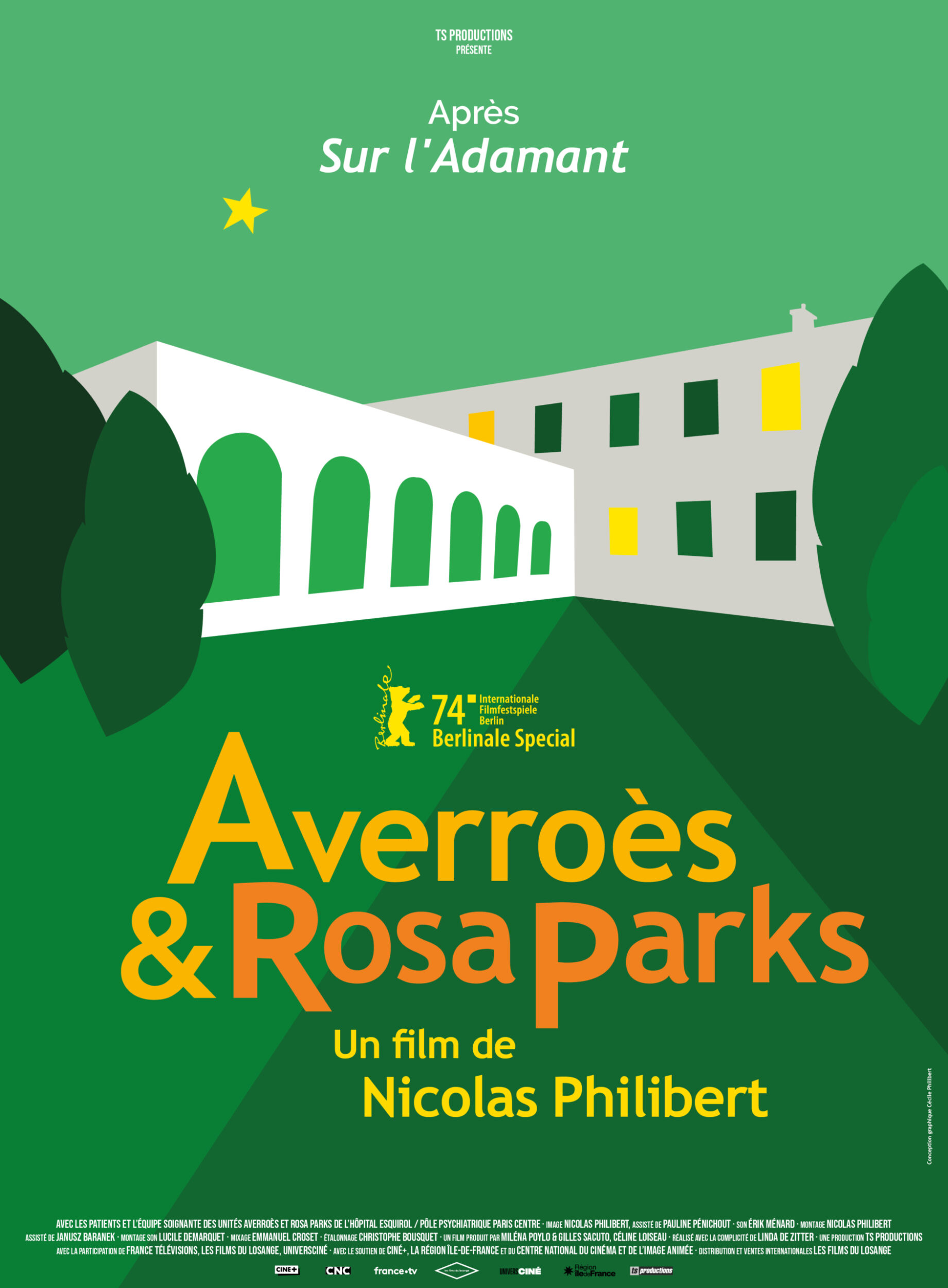

Averroes and Rosa Parks: two units of the Esquirol Hospital, which – like the Adamant – are part of the Paris Central Psychiatric Group.

From individual interviews to “carer-patient” meetings, the filmmaker focuses on showing a form of psychiatry that continually strives to make room for and rehabilitate the patients’ words. Little by little, each one eases open the door to their world.

Within an increasingly worn-out health system, how can the forsaken be given a place among others?

This film was made with the complicity of Linda de Zitter

Image Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Pauline Pénichout and occasionally by Katell Djian • Sound Erik Ménard • Drone shots Emmanuel Fraisse • Editing Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Janusz Baranek • Closing credits music Sarah Murcia and Magic Malik, based on The Ode to Joy (Ludwig Van Beethoven) • Sound editing Lucile Demarquet • Mix Emmanuel Croset • Colour grading Christophe Bousquet • Post-production supervisor Delphine Passant • Producers Miléna Poylo & Gilles Sacuto, Céline Loiseau, assisted by Clément Reffo, Coline Perraudin, Joseph Sacuto • Produced by TS Productions • With the participation of France Télévisions, Les Films du Losange, Universciné • With the support of la Région Île-de-France, in partnership with the CNC • With the support of Ciné+, Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée.

With the patients and carers of the Averroes and Rosa Parks intra-hospital units, Esquirol Hospital, Charenton-le-Pont.

French distribution & international sales : les Films du Losange

French release : March 20, 2024

Birth of a triptych, by Nicolas Philibert

Before I began shooting On the Adamant, I had told myself that this highly original day centre – built on water – was a sort of autonomous little island, not necessarily closed in on itself, but fairly self-sufficient, say. I of course knew that the Adamant was part of a greater whole, the Paris Central Group, that also includes two medical-psychological centres, a mobile team and two care units, aptly named Averroès and Rosa Parks, within the Esquirol Hospital – formerly known as “The Charenton Asylum” – but it was as if, afraid of spreading myself too thinly, I refused to see how complementary and interdependent these different structures were and how they formed, with the Adamant, a network within which patients and carers were continually urged to circulate, each one able to “build his or her own cartography between the different points of reference at their disposal”. Subconsciously perhaps, I had needed to detach the Adamant from its context as if to single it out more clearly.

Once there, I quickly realized that this off-screen world had to be given an existence, if only in an allusive manner, at the risk of falsifying reality. Images are always misleading, you may say, and relating what we see is only ever one reading among others, an interpretation, but, even so, completely masking this plural dimension would have been an aberration. While the Adamant attracted attention, the other structures, more classical, were no less essential. The two medical-psychological centres were snowed under with requests and it took months to obtain an appointment. At Esquirol, Averroès and Rosa Parks were continually jam-packed. Moreover, several “passengers” on the Adamant with whom I had good contacts were staying there. I am thinking notably of Olivier with whom I had shot a sequence at the drawing workshop that had overwhelmed me, or François, the man who would open the film – once edited – by singing La Bombe humaine. Tearing themselves away from the hospital required them to make a huge effort. Getting up, dressing, crossing the grounds and going as far as the metro were often insurmountable tasks.

One day, I decided to visit them there. The Averroès and Rosa Parks units share a single building around a tree-filled patio. Averroès is on the ground floor and Rosa Parks upstairs. Neon-lit corridors, doors fitted with portholes, small single or twin rooms, a TV room on each floor, a few rooms set aside for meetings, mismatched chairs, a self-service restaurant. On the diagonal of the patio, a welcoming greenhouse where the Tuesday “carer-patients” meetings, the Wednesday morning “bar” and the few remaining workshops are held. That day, Olivier was busy, but I spent two hours talking to François. The perceptiveness with which he related his experience of more than thirty years in psychiatric care made a strong impression on me.

I returned over the following weeks and met other patients. Some seemed to be on the edge of the abyss and avoided all contact. Others were happy to have someone to talk to. Romain, thirty or so, spent his days “watching the plants grow and doing magic tricks.” Great! He took a pack of cards out of his pocket and did several tricks for me that all failed miserably. He was a little put out but ended up laughing about it. Eva had been hospitalized “at the request of a third party”. This wasn’t the first time. “I become obsessed… When I grow fond of someone, I find it hard letting go, and it turns into harassment.” Myriam did not want the others to hear her story. We met in the TV room. As part of her therapy, she had just unlocked a traumatic experience repressed for forty years. Placed in the care of her uncle and aunt at birth, she was abused by her uncle until the age of five. If I came back with the camera, she would testify: “It will help me,” she said. But she would leave the hospital a few days later.

Each one of them seemed walled up in abyssal solitude. From one visit to the next, I noticed new faces. Absentees too. The rotation was unending. Some weeks, the shortage of beds was such that admitting a new patient meant that another had to leave. But which one? A headache. I met the nurses, the health auxiliaries, the psychiatrists, the psychologists, the social workers, the administrative staff. Many of the nurses and health auxiliaries were temporary hires. Everyone was under pressure. I cautiously expressed my wish to come and shoot “a few extra shots” that would help to create the link between the Adamant and the hospital. The idea was greeted warmly. Nearly everyone knew about the filming taking place at the day centre and they had clearly heard good things about it. I was invited to attend a meeting. Then the morning staff briefing. Then the Tuesday “carer-patient” meetings. Occasionally stormy, always colourful, it was not unusual to see a patient rebel, hurl abuse at the medical team, start railing against psychiatry, medication, living conditions in the hospital, the French Republic, the Vatican, the food, the coffee… Extra shots? Deep down, I felt I’d moved beyond that. The idea of a second film went through my mind. In it, I wished to focus on the consultations, those individual interviews between patients and carers. An approach that I had left to one side on the Adamant. It’s true that one-on-one interviews are less frequent there.

Yet, at the same time, a third film had already begun to take shape. A few days earlier, I had had the opportunity to accompany and film two eminent members of the Band at the home of Patrice after the latter’s typewriter had begun to play up. The Band is a small group of carers who are skilled with their hands and who, not content with restoring souls on the Adamant, occasionally go to patients’ homes to do odd jobs: fixing a bookshelf, unblocking a washbasin, mending a plug, assembling a piece of furniture, etc. Patrice is an emblematic figure at the day centre. Winter or summer, this seventy-year-old man arrives every morning as soon as the place opens, goes to sit at “his” table, drinks a coffee and, without any further ado, begins writing a poem in alexandrines. When he gets home, he settles down at his typewriter and transcribes the day’s poem. This highly regulated ritual seems to be what has kept him going for years. With his typewriter suddenly on the blink, he was in a terrible state. Walid and Goulven offered to stop by, without any guarantee of success. Both in their thirties, they had never seen a typewriter before… except in movies. They got to work. I filmed and recorded a beautiful scene.

This initial shift led to others. The members of the Band were called on regularly and other home visits awaited them. Why not keep following them? Restoring souls, repairing objects. A third film? Of course, this meant seeking additional funding, but for the rest, if I got organized… I began to believe in it. The three films would form a whole while remaining independent of each other: one could be seen without the other two. Three films within the same psychiatric department, each one of which would raise the curtain on a specific aspect of this psychiatric care that, despite the surrounding devastation, still strives to give priority to human relations. Each film would introduce new faces and reunite us with others.