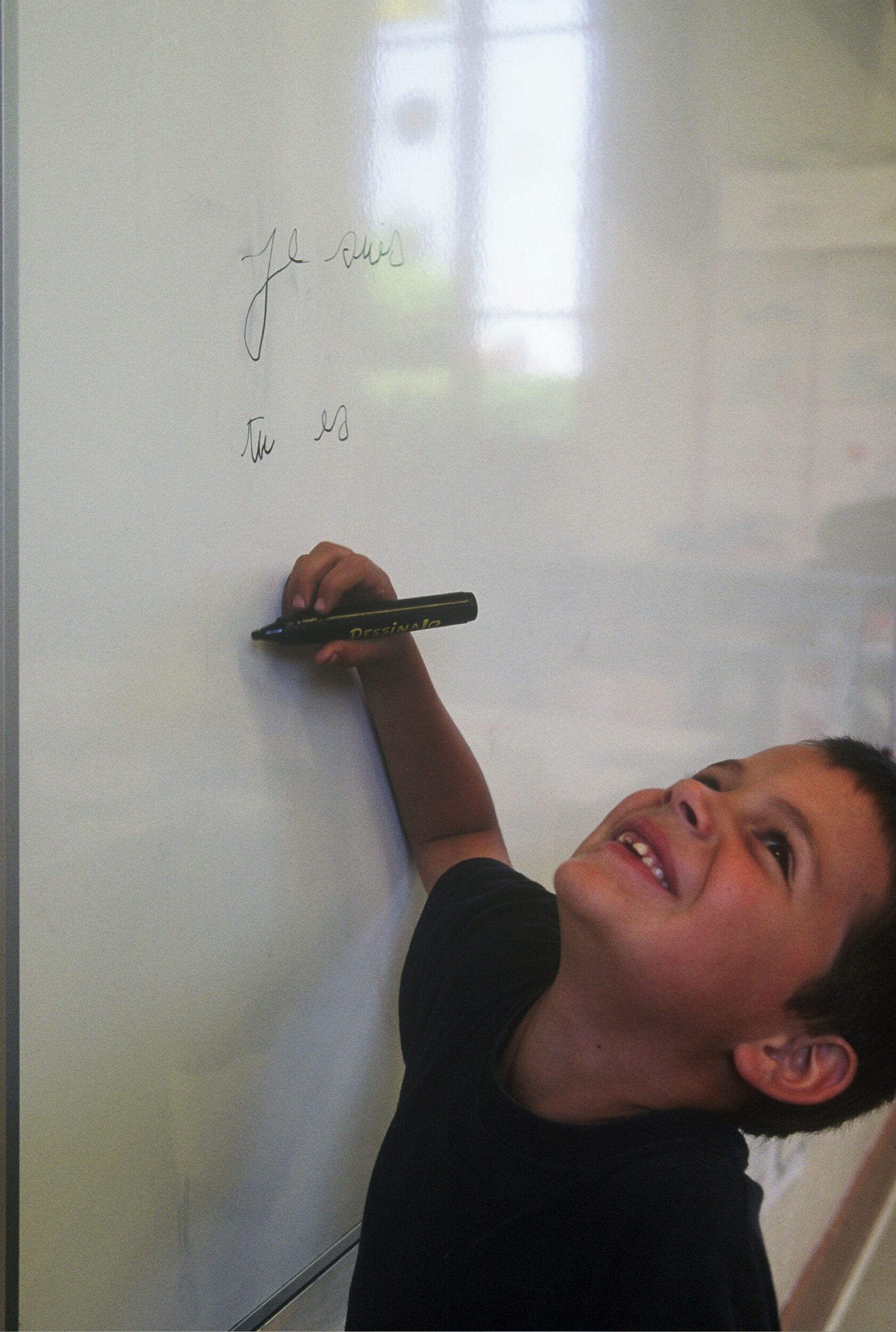

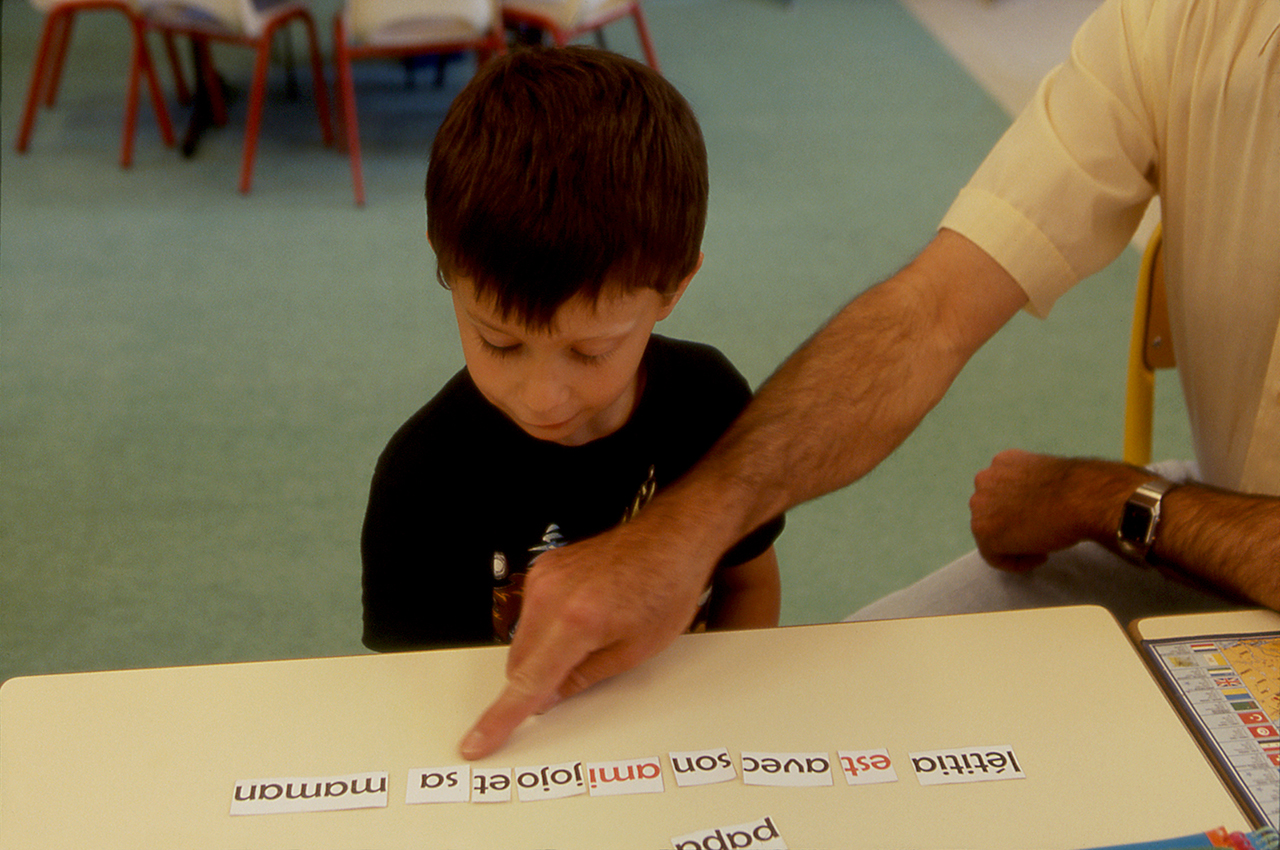

Daily life in a single class school in a small village.

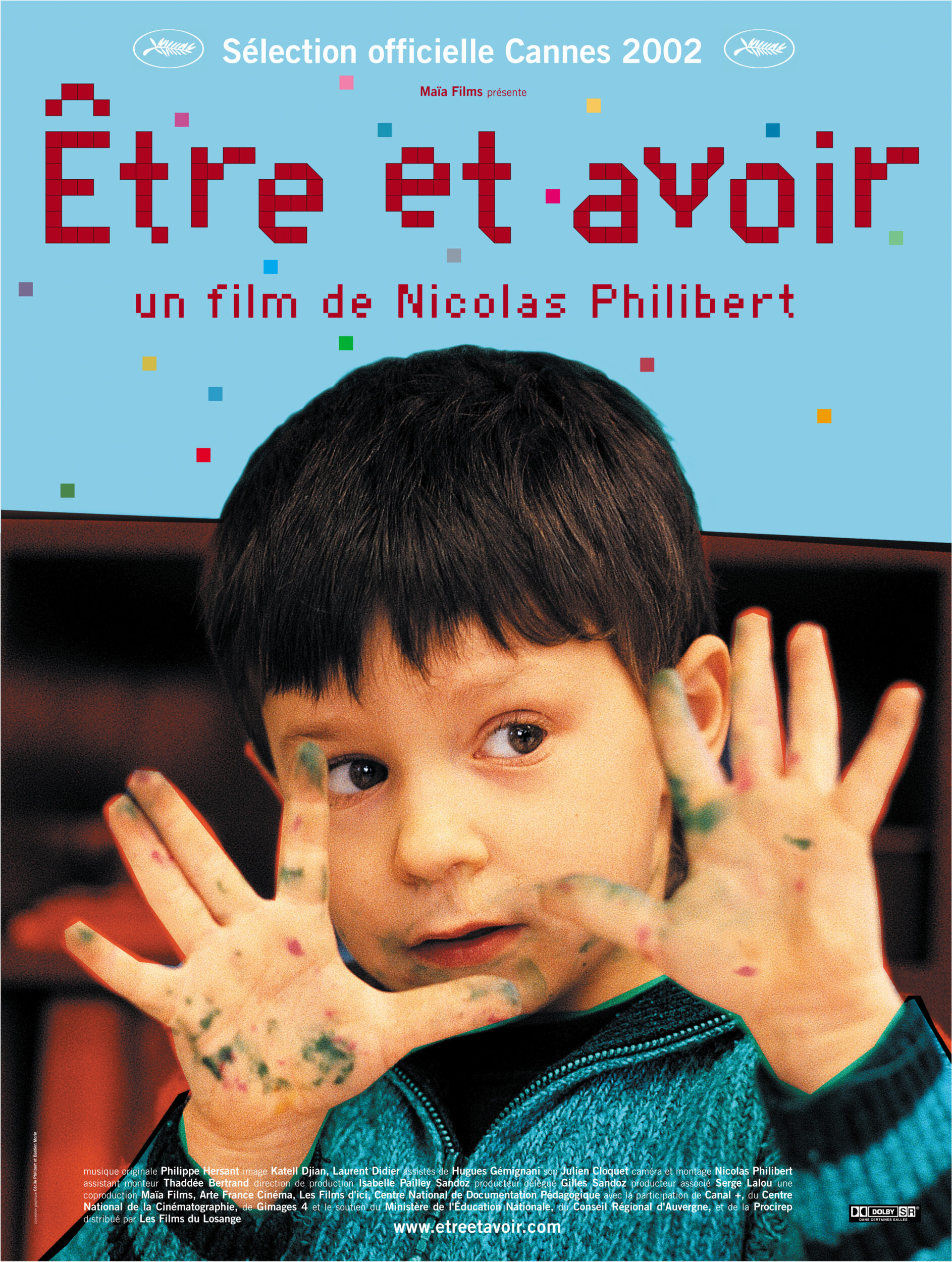

Photography Katell Djian, Laurent Didier • Camera Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Hugues Géminiani • Sound Julien Cloquet • Editing Nicolas Philibert, assisted by Thaddée Bertrand • Original score Philippe Hersant • Production management and administration Isabelle Pailley-Sandoz and Tatiana Bouchain • Producer Gilles Sandoz • Associated producer Serge Lalou • A coproduction Maïa Films, Arte France Cinéma, les Films d’Ici, Centre National de Documentation Pédagogique • With the participation of Canal +, Centre National de la Cinématographie, Gimages 4, and the support of Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, du Conseil Régional d’Auvergne et de la Procirep.

Sélection officielle Cannes 2002, hors compétition • Prix Louis Delluc 2002 • Prix « Tiempo de Historia », Festival de Valladolid, 2002 • Grand-Prix du Festival France Cinéma, Florence, 2002 • « Best documentary » (Prix ARTE), European Film Awards, 2002 • Prix Humanum, décerné par la Presse Cinématographique de Belgique, 2002 • Prix Méliès « meilleur film français de l’année » décerné par le Syndicat français de la Critique de Cinéma, 2003 • Prix des auditeurs du Masque et la Plume, France Inter, janvier 2003 • Nominations aux Cesar 2003 : « Meilleur réalisateur », « Meilleur film » et « Meilleur montage » • Cesar 2003 du montage • Prix de l’Association Cubaine de la Presse Cinématographique (Fipresci), Festival du Cinéma français à Cuba, 2003 • Etoile d’Or décerné par la presse française • Prix du public au 4e Festival du film français à Athènes, 2003 • Grand-Prix et Prix du public au Festival du Film francophone de Bratislava (Slovaquie), 2003 • Grand Jury Prize for the Best Doc., Full Frame Film Festival, USA, 2003 • « Best non fiction film Award », National Society of Film Critics, USA • Nominé aux BBC World Cinema Awards, novembre 2003 • Nominé aux BAFTA (British Academy Film Awards) dans la catégorie « Best films not in the English language », Londres, 2004.

Distribution France & International sales : Les Films du Losange.

French Release : August 28, 2002

“A camera gives you incredible power over others”, by Nicolas Philibert

I wanted to locate the film in a fairly mountainous farming region where the climate would be harsh and the winter difficult, which is why I focused my search on the Massif Central. Before choosing this school, I contacted more than 300 and visited at least 100. It was important to me to find a class with a smallish number of pupils (10 to 12), so that each child would be identifiable and could thereby become a character in the film. I also wanted the age range to be as broad as possible – from nursery age to fifth year of primary school – for the atmosphere that emanates from these small heterogeneous communities where children have to learn at a very early age to be independent, responsible for themselves, and mutually supportive. And then the classroom itself had to be quite large and sufficiently well-lit so as not to have to need artificial lighting.

At first, my search was a little haphazard. One teacher would send me to another and so on. But, after a while, to avoid covering miles needlessly, I decided to use the regional educational departments. This was no doubt more efficient but it took a lot of time all the same. I had to write letters, wait for replies… There was a great deal of wariness. This was only natural: a ten-week shoot in a class wasn’t necessarily obvious.

Of course, I was aware that a lot of things would depend on the choice of teacher, but I was very open-minded about this nevertheless essential factor. The teacher could be a man or a woman, young or not so young, experienced or otherwise… I had no foregone conclusions on that level.

Of course, each one had his or her own style and personality but the majority of teachers seemed to be extremely committed to what they were doing.

As for the educational methods, they varied from one class to another but that aspect was of secondary importance to me. What mattered was the general atmosphere of a class, not the different methods used to teach the children to read or calculate. I wasn’t making a film for specialists.

So why did I choose that particular class? The November half-term break was approaching, I had visited just over one hundred schools, I had been travelling around for four months and, when I entered that class, I felt I had found what I was looking for. The room was large and bright, the number and age of the children matched what I was looking for and I felt that with this experienced teacher and his slightly authoritarian attitude, our presence wouldn’t be too much of a burden. He seemed fairly receptive and ready to welcome us for 10 weeks. At the same time, he had a secretive and mysterious side that made him a “character”. Finally, I felt that choosing a man, when 85% of people doing this job are women, would reinforce this intriguing side and so fuel the audience’s imagination.

When I first met him, he seemed surprised that someone could make a cinema documentary on such an unspectacular subject. I explained my approach to him, specifying that it was founded neither on the picturesque nor the nostalgic but on the desire to follow the work and progress of his pupils as closely as possible. I was convinced that filming a child grappling with a subtraction could turn into a genuine epic tale…

The parents quickly gave their agreement. When I met them for the first time, I felt that it was important to tell them that their children would not always be shown in the most gratifying light, because otherwise there would be no film – or at least no story. I also did the groundwork concerning editing, telling them that we would have to get rid of hours and hours of dailies, and probably sacrifice some lovely scenes, in the knowledge that a film’s final cut is not a “best of”, but a construction, which complies as much with the director’s desires as with laws peculiar to film, meaning that, at the end of the day, their children would probably not all have equal screen time… In a nutshell, to avoid any kind of ambiguity, I was keen to assert right away the subjectivity of my gaze. From that point on, each of them was free to agree or refuse. If a single parent had been reticent, I would have changed schools.

Filming lasted a total of ten weeks, in several sessions, between January and June 2001. On day one, we took all the time we needed to explain to the children how we were going to work, and what our various gear was used for… They all looked through the camera, played with the zoom, and put on the headphones… Then their teacher took over, they went back to work, and so did we.

There were four of us in the crew: a cameraman, a sound engineer, an assistant cameraman and myself. From a technical angle, it was very complicated. The sound engineer had to cover the whole classroom on his own and by definition we never knew ahead of time what would come to pass. Where the camera was concerned, there were countless pitfalls; we had to be permanently on the alert for our reflections in the window and on the blackboard. The decision not to add any lighting to the existing neons did not allow for much depth of field, and, as a result, no margin of error for focusing. But this is part and parcel of this type of filming, and it makes everyone give the best of themselves.

People have often asked me how we managed to get ourselves forgotten but that wasn’t the problem. Of course, we were as discreet as possible so as not to hamper the smooth running of the class, but the problem wasn’t getting ourselves forgotten. What mattered was getting ourselves accepted and that’s a totally different matter! Trying to get yourself forgotten would be like wanting to film people without them knowing, in secret, to steal something from them. My camera wasn’t a surveillance camera! On the contrary, we had to be there. At their side. Present in what they were doing. To show them that we weren’t there to break down doors, to film them at all costs, in any circumstances. Nor to judge them. At times, we had to be able to give up and put the camera aside. In the class, there were some children I didn’t film much at all, especially among the older ones. The camera bothered them. For instance, I often filmed Jojo but rarely Laura, his sister whom the camera intimidated. We had to be very attentive. A camera gives you incredible power over others and the whole question is knowing how not to abuse that power. It’s often very difficult! It’s easy to get carried away when things start happening! If a child was uneasy, if he didn’t want to be filmed in certain situations, he wouldn’t always dare to say so in front of his friends.

It was necessary to find “the right distance”, a distance that varies according to the context and the nature of the relationships that you have with the persons that you film. Each film is a singular story and this question of limits is posed over and over again… A film imprisons the people that you film in a certain image, at a precise moment in their lives and you have to remember that this image will stick to them, that they won’t always be able to rid themselves of it. That’s the whole difference between documentary and fiction.

The moment when the teacher asks Olivier about his father’s health cropped up in a very unexpected manner. At first, when I started filming their conversation, all that they were talking about was work. The teacher was trying to encourage Oliver: if he didn’t want to repeat the year, he had to try harder. Then, all of a sudden, he changed the subject, asked how his father was doing and Olivier burst into tears! Behind the camera, I felt distinctly uncomfortable! During editing, I hesitated for a long time about keeping this scene. The same was true of the conversation between the teacher and Nathalie, which I kept, also after a great deal of hesitation. I felt that when the time came, when they would discover the film, both of them would be strong enough to confront these images.

The seasons, passing time… those were vital for me. Often, after class, we would set off along local paths to film landscapes. I wanted to film nature in its beauty and also show its disturbing side. In fact, if the film has something of the fairytale about it, it owes it first and foremost to these shots: to the slightly ghostly trees swaying in the wind, to the silence that weighs down on these wide open spaces, to this loneliness, to the fields of barley where they look for Alizé…

The film often plays on this opposition between the interior and exterior, between warmth and cold. On the one hand, school, the heat of the stove, the fact of all being together in a sort of protective cocoon; on the other, the vastness of the world, its violence, the unchained elements, snow, wind, storms, the cows that the farmers try to herd together…

In following the “characters” of this class, I wanted to share their ordeals, joys and minor tragedies. It is a very open film. For my part, I see a certain serious side to it, even a certain violence, although this remains contained. Before filming, I had forgotten just how hard it is not only to learn, but also to grow up. This plunge into the world of school gave me a powerful reminder of that. Perhaps that is the film’s true subject.