All About Memory and Madness

The French nouvelle vague has left barely a ripple, but French cinema has not lost its capacity to shock and entertain. Its vitality is due in some part to the French government’s subsidies to filmmakers, which have encouraged a handful of original and talented filmmakers : documentary maker Nicolas Philibert is perhaps first and most subtle among them. A man who hates being told what to think, he refuses to ram his own ideas down others’ throats.

« My approach is the opposite of Michael Moore’s » he says. « He’s right to attack the gun lobby and the health system but the way he does it is manipulative. He treats his audiences like children. »

At 56, the slight, soft-spoken Philibert has directed 15 films that treat viewers as adults. They are about people and their relationships at work, study, and play. « Just because they’re not ostentatiously militant it doesn’t mean that they’re not political » he says. « Making people think is political. » He belongs to several activist film associations, believing that Nicolas Sarkozy’s center-right government is bad news for quality film and that the threat of homogenized art always lurks.

Philibert’s best-known movie is 2002’s Etre et Avoir (To Be and To Have), about a one-class school in the Puy-de-Dôme, where on and off he spent a year filming the village teacher and his 12 pupils, aged four to 10. Ostensibly it is about education but in fact it’s about how difficult it is to grow up. Philibert says he himself changed schools often because « I didn’t adapt well to childhood. I suffered. I was an anxious, worried child. »

An unexpected hit, Etre et Avoir has so far been seen by close to 2m people in France and many more round the world. « It’s the biggest-grossing non-wildlife French documentary ever » Philibert says, laughing (he mentions Microcosmos and March of the Penguins as its rivals). But the triumph turned sour when the teacher, Georges Lopez, sued the production company, claiming intellectual authorship. A handful of parents sued for money as well. After four court cases, the victory was Philibert’s but it left a

bitter taste. He refuses to talk about the experience, except to say that the solemn, bearded teacher was a far more complex person than at first appeared.

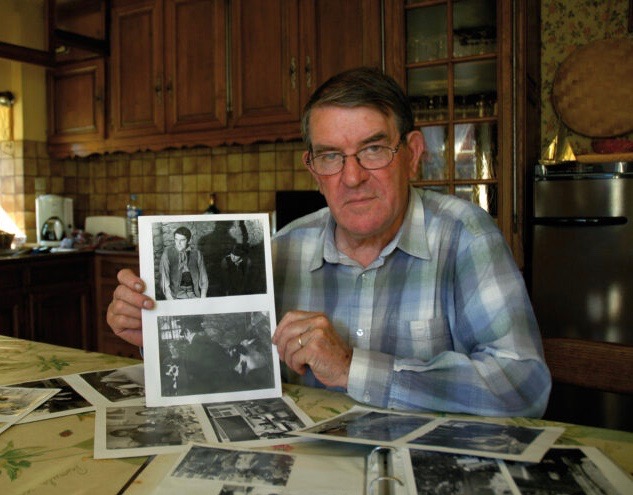

His new multilayered documentary, « Retour en Normandie », touches on memory and madness, reality and acting, death and fathers and making films. It started as a trip back into the past and the three months in 1975 when Philibert worked as an assistant to René Allio, a French director who is virtually forgotten today, even in France.

When lecturing students at Femis, France’s national film school, Philibert was shocked to discover that they hadn’t even heard of Allio, although it was only 10 years since he had died. But he stresses that his film is not a homage to Allio, nor does it require familiarity with his work — it is its own story, although it uses Allio¹s earlier film as a springboard. Recent audiences at the London Film Festival and the Dublin Festival of French Film gave it a warm, even emotional reception.

Allio’s film, Moi Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma soeur et mon frère.. was the true story of a young peasant in 19th-century Normandy who slaughtered his mother, sister, and brother because of the cruelty with which they treated his father.

His spectacular trial involved some of the finest lawyers of the day and touched on issues of madness and responsibility. What made the case of Rivière – an uneducated boy seen by many as the village idiot – unique is that before he hanged himself in his cell, he produced 80 beautifully written and tightly structured pages on his life and crime with barely a word scratched out. « His text showed considerable memory, acuity, and intelligence, » says Philibert. Allio’s film is based on a work edited by the philosopher Michel Foucault, who was fascinated by the case.

Allio cast the residents of a village near Caen to play Rivière’s family and their neighbors, and used professional actors to play the lawyers, doctors, and judges. For his own film, Philibert returned to the village and met many of the locals who had taken part in the first movie, asking them about the impact it had on their lives. Most were affected in one way or another. The film meanders from interviews to shots of farmers at work, a literary archive, an anti-nuclear march, a psychiatric clinic, landscapes, but through its apparent randomness runs one common thread: the interaction between people, the links that create a community and the continuity down the generations.

« I wanted to show how movies can act secretly, subterraneously within each of us, » says Philibert, « and how they can help us open our eyes and grow. »

Philibert is part of a generation of documentary makers who have long cast aside the illusion that there is such a thing as objective reality. His other films include La Ville Louvre (1987), showing the backrooms of the Paris museum before its reopening after the installation of I.M. Pei’s pyramid, and a subtly moving documentary about deaf people, Le Pays des sourds (1992), which showed the complexity of deafness, and made it obvious why one man touchingly expresses his disappointment at having a child who isn’t deaf. In all his films he stands slightly to one side, never going for the obvious, always giving the viewer breathing space.

Philibert sees documentary as a form of artistic expression as powerful as fiction. « People say : ” That was good, but when will you start to make real movies ? ” He laughs. But there is no such thing as pure reality, he argues. « Ask 10 filmmakers to film the same event and you’ll have 10 different films, » he says. « There’s always a misunderstanding that because documentaries show real people in real situations, what you see is objective reality, when everything from the shots, their length to the angles and sequence of images offers one person’s view. »

Ever since La Moindre des choses (1996), which centered on the staging of a play at a psychiatric hospital, Philibert has edited his own films, enjoying the freedom of not having to explain what he wants. When you work with an editor, they say: ” Why are you putting this shot here? ” But I can’t explain everything, it’s very intuitive work, almost poetic. I’m much happier this way. I like that solitary voyage. »