Norman inquests

Films that might properly be described as « philosophical » – insofar as they are cinematic enquiries into the existence, nature, meaning and interrelatedness of things (including, of course, cinema itself) – are rare indeed. And philosophical films that are wise, warm, witty and intellectually accessible are even less common. But such films are characteristic of the oeuvre of documentarist Nicolas Philibert, who until the success of Être et avoir (2002) was perhaps French cinema’s greatest secret.

Take, for instance, his two museum movies La Ville Louvre (1990) and Un animal, des animaux (1996), which move beyond being accounts of institutions to reflect on notions of taxonomy, language, knowledge and, in the latter, the gulf between life and mere physical existence. Then there are Le Pays des sourds (1992), a consideration of communication and community, and La Moindre des choses (1997), a meditation on mental illness, psychiatric therapy, performance and belonging. And Être et avoir itself is a study of social change and educational theory in which, in one of many memorable scenes, we watch a small boy come to grips with the concept of infinity.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Philibert’s documentaries delve into epistemology, ontology, psychology, language and identity : his father Michel – whose weekly film-club screenings of Bergman, Dreyer, Bresson et al would greatly influence his son – was a professor of philosophy and Nicolas himself graduated in philo. But it’s the compassion, clarity anc poetic resonance of his work that take it beyond the academic ; indeed, his latest film Back to Normandy (Retour en Normandie), his most richly philosophical and multi-layered work to date, is also immediately notable for its subtlety, delicacy and humanity.

On the surface, at least, this first foray into confessional « first-person » cinema has a straightforward premise : Philibert revisits rural Normandy to catch up with old acquaintances three decades after he first met them. But this isn’t just a look at the changes in these people and the world they inhabit in the manner of Michael Apted’s Seven Up films or Louis Malle’s God’s Country. For Philibert met the individuals in question when he was looking for locals to cast in director René Allio’s 1975 film Moi, Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma soeur et mon frère... So his own movie is in part about the relationship between cinema and life.

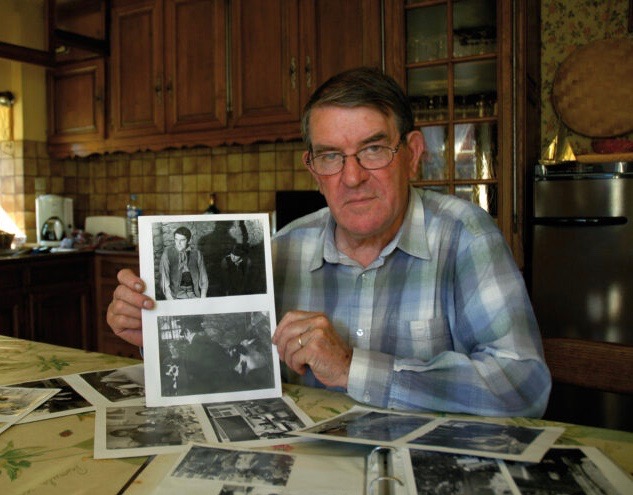

« The adventure of working on Allio’s film affected me deeply, » says the quietly spoken and engagingly boyish 56 year-old. « I was young and I was suddenly given a lot of responsibility – persuading people with no experience of cinema to participate in the film wasn’t easy. But there came a moment when they realised it was a serious project – a film maker from Paris had come to exhume a story that belonged to them. »

The story in question involved the 1835 murder by a young man of his mother, sister and brother close to the area where Allio wanted to shoot his film, which was in turn inspired by a book of the same title published as a collective research project led by Michel Foucault, the philosopher famed for his interest in the history of crime and punishment, madness and the law. Foucault was fascinated by Pierre Rivière’s arrest, trial, imprisonment and death not so much because of the crime itself – indeed, in his foreword he claims that parricide was quite common at the time – but because they generated so many documents : legal, medical and forensic records and testimonies by those who knew the family but also – rare at the time -reports by psychiatric « experts ». Moreover, there was an elegant, insightful 8o-page memoir written in prison by a culprit widely regarded as mad or simple and who described himself as someone who could « only barely read and write ». Allio too was fascinated by the case and was determined to restore to the Normandy farming community a slice of its own history by recruiting locals to play the peasants in the film while the judiciary and other figures of authority were represented by their 20th-century counterparts, Foucault included.

« Meeting those people again was just the starting point for my own film, a pretext, » says Philibert. « From the outset I knew I’d also use extracts from AIlio’s film and because the project’s roots lie in my own memories I knew that for once I’d relate the film in the first person. Not like Michael Moore – I’m not at the centre of the world depicted – but t too had something to tell. I worked with Allio before the villagers came on board, so I also knew about his problems with financing and his struggle to get the film made.

« Obviously I didn’t want to make a sequel to Être et avoir, especially as things ended up going badly on that. [Protracted court cases were brought against Philibert and the film’s producers by the teacher who appeared in it, who claimed that as one of its creators he deserved a full share of the profits.] Perhaps there’s a link between the unhappiness connected with that film and my desire to make this one, which revisits a very special, happy experience. Certainly Être et avoir’s success made it a little easier to find money for this one. And my obsession was to make a film that could be understood by anyone, including those who’d never heard of Allio or Foucault. Ifs not for specialists – it’s just about a film-maker going back to examine the traces on people’s lives of making another film 30 years earlier. »

One of Back to Normandy ‘s central themes, then, is memory. Besides Philibert’s own recollections, his interviews with villagers reveal that the production of Allio’s film was an illuminating experience for most of them and even had a profound effect on some, particularly Claude Hbert, the young loner cast as Pierre Rivière. But then there is also Rivière’s own remembrance of his life, and this written account leads Philibert into an investigation of different forms of documentation. Details of the murder were initially documented not only by the culprit but by a great many witnesses, experts and journalists; over a century later these records were analysed by Foucault and his team; their book inspired AlIio’s account of the crime in the form of a filmed docudrama; and now Back to Normandy constitutes one more document, concerned not only with the crime and the ways it has been represented but with its resonance in the lives of the director and others. All these levels of narrative – likened by Philibert to Russian dolls – are interwoven into a clear, coherent movie. So how did he go about planning the film?

« To make a film I need just one strong idea to begin with – in this case, meeting the people in Normandy again. After that anything can happen, and even more than in my other films I made this one up day by day. Sometimes I had to prepare in advance, as when I needed authorisation to shoot in the prison or wanted to interview a whole family, but otherwise it was very improvised. One idea would lead to another, one encounter would lead to another, something else would lead nowhere at all. The villagers saw me filming different things here and there and wondered howl could construct a film from such diverse elements.

« When I’m shooting I simply have a desire to make a film about a whole range of things, without knowing how I’ll combine them. I only really find the film during the editing : in this case I had about 6o hours of footage, so a lot was left out. To use a psychoanalytical term, I edit by association. Sometimes I’m fully conscious of why I’m putting things together; in other cases it’s less clear what the precise link is. When I made my first film His Master’s Voice with Gérard Mordillat, who was the other assistant on Allio’s film, we edited it entirely according to what the interviewees said, creating a logical narrative from their words. But when we screened it we realised that it didn’t work because we’d failed to take account of the intonation and rhythm, how they looked, and so on. So we changed it. I’ve always remembered that : you shouldn’t get too theoretical about what you’re doing. Sometimes it’s more important to have faith in your intuition, otherwise things can turn out dry and academic. »

It’s hard to imagine such charges being levelled against Back to Normandy, which ranges free and easy, far and wide, from its opening sequence of a piglet’s troubled birth through scenes of the villagers reminiscing or going about their business, clips from Allio’s movie, shots charting Philibert’s voyage of rediscovery and – the only scene in this tender, touching film that’s remotely difficult to watch the butchering of another pig. The sequence comes shortly after shots of the prison in which Rivière was held and eventually died : was that link a deliberate parallel ?

« I can’t explain everything I do and some choices aren’t part of a grander metaphor. For me the butchery sequence was primarily about work and about the pig farmer Roger. In fact, my producers wanted me to remove the footage of the butcher talking before he kills the pig so as to make the slaughter feel more metaphorical. But I said no. A metaphor for what ? I just wanted to show that there’s a violent side to Roger’s work which is an integral part of the everyday existence of many country people. »

Philibert’s compassionate curiosity about people’s lives and his unplanned approach can lead to fortuitous but fruitful discoveries. Those who’ve seen La Moindre des choses will not be surprised by his interest in the psychiatric aspects of the Rivière story, but the fact that Annick Bisson, who as a girl played Rivière’s sister in Allio’s film, now works with the mentally handicapped was something the director was unaware of until he started filming. Moreover, his longterm fascination with language finds poignant expression in his encounters with two villagers : one woman who has speech problems due to the onset of mental illness in her family and another who suffers from aphasia following a stroke.

« Before starting on this project I spent three months attending hospital sessions for people suffering from aphasia and t was considering making a film about the condition. Then when I went to Normandy and learned that Nicole had lost her power of speech, 1 found it very moving because she’d always been a rather militant person, accustomed to using language to make political points.

« For me this is partly a film about l’après : what happens after a film is made. For directors of fiction it’s less important because your actors can go off and act in another film, but when you make a documentary it’s usually a one-off in people’s lives. With La Moindre des choses, for instance, it was essential to return several times to the psychiatric clinic to talk with the people I’d filmed before I showed them the movie. I needed to prepare them for what they’d see: for how they might see themselves, but also to ensure they didn’t think things had been cut because they were less attractive or clever than others who appeared. I had to help them understand that a film is always a narrative construction, not a « best of » or a competition.

« Of course, one of this film’s themes is cinema as collective or familial experience. Allio’s film brought together a very diverse group of people, Parisians and country folk, young and old, who had a great curiosity about each other and developed real affection for each other. And everyone, even now, has fond and vivid memories of that experience.”

Not that Philibert’s film is in any way sentimental : just as it reveals that rural life has a bloody and violent side, so it admits to both the virtues and drawbacks of familial bonds, the strength and vulnerability of communities, and the potential and limitations of film as an enduring form of documentation. And while his passion for cinema as a means of expression is gloriously evident in the poetic beauty of his images – see him capture, for instance, the improbably balletic grace of cows walking through a farmyard – and in his discreet deployment of sound (some of the music was composed by his maternal grandfather), he never romanticises the medium, even showing the Eclair labs to remind us that film is part of the chemical industry.

« Cinema is often a product of obstinate ambition. I was lucky to get my start with Allio, a real artist who had been a painter, then a theatrical set-designer, and made his first film when he was in his 40s. His films were contemporary with the nouvelle vogue but he was never part of it or of any other fashion. He never had a hit, never rested on his laurels, and was always looking to do something new. He was important in giving me confidence in myself and I had a very strong dialogue with him over the years, right until his death. So this film is also about fathers : Pierre’s father, God the father – who is invoked by several people – Allio, who was a paternal figure to me, and my own father. That’s one theme I did know I’d be dealing with from the start. »