Looking at the world to reconstruct it

After Être et Avoir (To Be and To Have), which was so successful, how did you come up with such a different project as Retour en Normandie (Back to Normandy)?

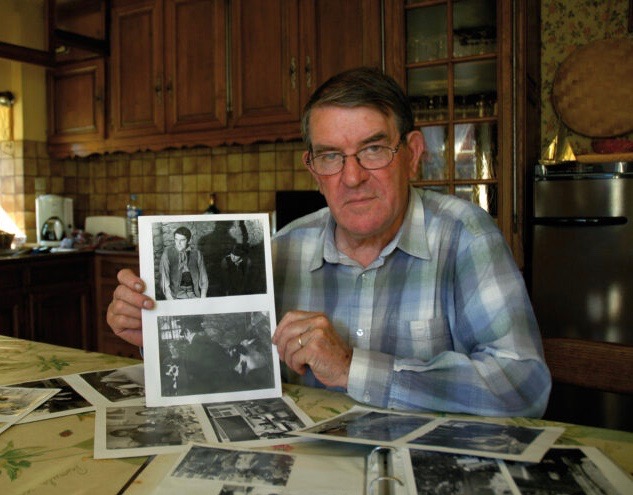

After the success of Être et Avoir, I was looking for something to take me back to my sources, to my roots. The filming of Moi, Pierre Rivière… was a fundamental experience in my life. In 1975, I worked as assistant under the director René Allio filming a feature-length fiction film based on a true story which took place in the French countryside in 1835. A young farmer killed his mother, sister and brother, and fled, hid in the woods for a month before getting caught and, then in prison, asked for paper and ink. The lad who everyone took for an illiterate halfwit started to write an extremely long, magnificent, highly surprising text revealing not just an extraordinary memory, but also lucidity. While working in 1972 on the relationship between Justice and the principles of Psychiatry, the philosopher Michel Foucault discovered the text and published it together with all the files from the trial. When Allio made the film, he sought out Normandy farmers to play some of the main roles, including that of Pierre Rivière himself. Thirty years later, I decided to go back to the scene of the crime to seek out these “actors”, find out what they had been up to since and shoot a film with them.

Why was the shooting of Moi, Pierre Rivière… so important to you?

It was one of the most intense experiences I have ever had; a human adventure. Back then, the idea of giving the leading roles in a film to non-actors, to country folk, was a fairly unique decision, unheard of in French film. I travelled around Normandy with my friend Gérard Mordillat in search of people who fitted the characters and were prepared to take part in the film. Those encounters were incredible. It was a thrilling, but difficult and uncomfortable experience… three weeks prior to shooting, we still didn’t know if there was enough money to make the film or not. Shooting was hard work too. Allio did not expect any less of his country actors than he would of professionals. He made similar demands of them. He wanted them to work as professionals even though they weren’t. And so, in the group we all formed, we never felt any kind of division between the film crew and the farmers. We were all living the same project. With the benefit of hindsight, I have been able to gauge the importance of this film in my life. It has never left me and, without doubt, runs like an underground river through my own work. Maybe because, to a certain extent, it approaches that duality between fiction and non-fiction which I was talking about earlier.

Retour en Normandie is the first of your films in which you openly speak. You thread the plot. What limitations and possibilities does such personal involvement imply?

I don’t use voiceovers very much, and ones of my own voice even less, but in this case, it was the logical thing to do because it was about a film so deeply rooted in my own personal memory. Despite speaking about quite personal matters, I didn’t hold myself back. I don’t like bragging about or exposing my private life. You ask about limitations, but the truth is that I felt I had total freedom in creative terms. Both in terms of tackling matter and approaching a subject so different from anything I had done before. You never want to resemble yourself, you want to get away from what you’ve done before and try out unbeaten paths. If there was unity of time and place in my previous films, then this time I took up position in three periods of time.

It’s true that Retour en Normandie breaks the distance with which you have always portrayed reality. But there is obvious continuity of your previous work in the subjects dealt with…

I can’t deny it. It looks like a film by another director, but if you dig a little deeper, then you’ll find that it has a lot in common with La Voix de son maitre (His master’s voice) (1978), Le Pays des sourds (In the Land of the Deaf, 1992), with La Moindre de choses (Every little thing) (1996), with Être et Avoir (To be and to have). They all look into how individuals express themselves, communicate with others. I don’t understand where this obsession comes from, but, true enough, I return to language through the aphasic woman, Allio’s notebooks, Rivière’s writing, which I consider very important. Another obvious similarity is the portrayal of people in their working environment. I like filming people working…

Was it during editing that you decided to end the film with the scene of your late father, Michel Philibert?

It’s one of the images I added at the end, indeed. From the outset, I wanted to find one of the scenes from Moi, Pierre Rivière… which had my father in it, but which were all cut out in the final edit. Of course, I didn’t know if I was going to find one and didn’t know where I could put one in my film. I didn’t find the scene until the final, final edit. I looked in La Cinémathèque française, in the Toulouse Film Archive, in the Swiss film Library… but there wasn’t a trace of the long version of the film, until finally, when I had given it up for lost, I asked at La Cinémathèque française again and, miraculously, it appeared. In fact, I already had a picture of my father taken during the shoot and, if I hadn’t found that scene, then maybe I would have used the photo. That brings us back to one of your earlier questions, about one’s reluctance to speak about oneself. On the one hand, I very much wanted to include that scene, but, then again, I was afraid of using something too personal in the film. It was a tough decision.

What made you decide to include it in the end?

The fact that the subject of fatherhood, of filiation, runs throughout the film. It is one of its main themes. The first person I visited was Joseph Leportier, who played Pierre Rivière’s father in Allio’s film. In fact, Pierre killed his mother and his brother and sister to protect his father. The father figure is present throughout the film, right from the moment I look back on René Allio, my filmmaking mentor, another father figure for me. Michel Philibert, my actual father, was the person who transmitted his love and enthusiasm for film to me. This film also talks about legacy, transmission, filiation, about what one generation gets from another.